Working In East Lothian’s Forests

Member of the British Honduran Timber Corps standing by logs awaiting removal.

Extracting East Lothian’s Timber

Timber was a key home-grown raw material in wartime Britain. However, extracting it from inhospitable areas was quite a significant headache for the authorities since conscription had removed many professional foresters and, as a result, there was an immediate scarcity of homegrown labour. Many of these timber-rich areas were in Scotland, not least in East Lothian itself, and two significant groups of foreign workers were ‘recruited’ to plug the gap and to bolster the extraction effort: the first came from Newfoundland and the second from British Honduras (now Belize), Britain’s only colony in Central America.

Newfoundland Timber Corps members with some local girls.

Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit

The scarcity of trained forestry workers in the UK led to a call for volunteers from Newfoundland, Great Britain’s first unofficial colony overseas. Strong traditional ties bound Newfoundland with the ‘Mother Country’ and the call was quickly answered. Edgar Baird of Gander recruited many of the men and a force (civilian not military) of some 300 men set sail to the UK in December, 1939, arriving in Liverpool on the 18th with the full contingent of 2,150 arriving by February 1940. Some 3,600 Newfoundlanders ultimately served in this capacity. Thirty-four died died as a result of accidents or illness and 540 of them later enlisted in the British Armed Forces. It was a magnificent effort.

The final group of foresters returned to Newfoundland on 26th July, 1946, having been asked by the British Government to remain at their work for a further year after the war’s end. Early in the war a group of these men came to Elmscleugh where they worked on local forests for some five months before moving north to areas around Inverness. The timber extracted was used largely for pit props (East Lothian alone had some eight working coal mines during the war), pier repairs and for beach defences (see “Defence against Invasion” section). The men’s first task was to build their camp accommodation!

Lewis Jenkins (on the left) being interviewed by Drew Scott.

Eyewitness: Lewis Jenkins - Member Of The N.O.F.U.

Lewis Jenkins was one of the Newfoundland group which came to work in East Lothian. Lewis hailed from Jenkin’s Cove in Newfoundland and, a twenty year old, had come over in the first group in 1939. He went home after the war, but finding no suitable work, returned and remained to live in the Dunbar area ever since. Lewis was unusual in one respect: a tussle at school over a pencil had gone very wrong and the pencil had pierced his left eye. He’d lost the eye but this didn’t stop him both from becoming a good forester and from becoming an accurate shot with a rifle.

Lewis gave this account of his experiences in East Lothian:

"We were born in Britain's oldest colony and when they called for volunteers for the forestry, well, that's why we volunteered. Three hundred came over in the first group and we landed in Liverpool and went by train to Kielder. That was a German PoW camp in the First World War. We were cutting timber to keep the mines going and were there eight or nine months. They needed props and all those things to keep the roof up in those days. I began as a cook and then became a lumberjack.

After we'd finished at Kielder we went for a short time to Plachetts [near Kielder] and then to Castle O'er, cut out the bit of wood there and then we landed up in Elmscleugh, near Dunbar. There was a lot of timber there then. We sent wood all over England and we cut the timber for the sands at Belhaven. It was all done to stop the Germans landing or dropping in men. In Elmscleugh we cut the timber and loaded it on to trailers and wagons and it went down to England. Once I was helping to load timber onto railway wagons at Innerwick station [16th August 1941] when a German aircraft flew over and machine-gunned us. The bullets went ping, ping, ping and we had to dive into an empty wagon to avoid being hit. One man was killed [Robert Faichen - railway worker].

[Naturally our food was rationed like everyone else’s.] We had one egg a week and two ounces of butter a month. Lunch was three slices of bread and a tin of corned beef. We had to sweeten our tea with strawberry jam! The huts we lived in were wooden and in the winter the walls were white with frost - on the inside! We used paraffin lamps at night and provided our own entertainment.

We were about five to six months [in Elmscleugh] and then we had to shift up north to just north of Inverness. We had our own sawmills up there. We didn’t return to East Lothian and when it was all over we were told overnight that we were going to Liverpool and then to St John’s. We were going home. When I got home I found that the only work was in the timber trade [so I] came back to Scotland. I worked in the timber business with Dickson and after that I went to the Belhaven Brewery for twenty-eight years.”

Lewis at the site of the Elmscleugh base of the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit.

The present day buildings house chickens, etc.

The Newfoundlanders And The Home Guard

Many of the foresters, like Ernest White and Lewis, also answered the call to join the East Lothian Home Guard, joining one of the local units. Later, when the work was largely finished in the south of Scotland and the Newfoundland foresters were posted further north, agreement was reached for the Corps members to form their own Home Guard unit. In this respect they were unique, as they thus formed the 3rd Inverness (Newfoundland) Battalion Home Guard, the sole Home Guard unit formed solely from men from overseas. Lewis relates his experiences below:

“They asked us to volunteer for the Home Guard since it was all open, the Germans could have come in, so we joined the local Home Guard though we had our own flashes, the Newfoundland flash on our shoulder. We weren’t allowed to wear our uniforms except when we were on guard or on manoeuvres. We couldn’t go out with it on because we weren’t in the Services. That’s why, when we went back to Newfoundland, they wouldn’t recognise us because we were civilians. However, now they’ve recognised us officially because we were in the Home Guard. It was only lately we got the Volunteer Medal. The Canadian military wouldn’t let us use the Legion but that’s all changed now we have the Volunteer Medal.

[When we joined the Home Guard we were] given five bullets to fire at a target at 500 yards distance. I overheard the Sergeant overseeing the recruits firing reporting to the officer that ‘one of those crazy Newfoundlanders is shooting at the target with both eyes open!’ The major told me ‘Man, shooting like that you wouldn’t hit a barn door!’ I, however, proceeded to place all my bullets in a six inch grouping, including two bull’s eyes, and the Major said nothing more. I was made a sniper up in the trees after that.

We used to have mock battles at weekends. There were so many men from North Berwick and ourselves: we had to capture them and they had to capture us. [On one occasion] in 1941 we were called out because the searchlights in a field at Woodhall was [manned] by Regular soldiers and a German plane came over and dropped two bombs between Woodhall and the Brunt Glen because it was trying to bomb the searchlights [near] the house I am living in now. ...one bomb went off in the field and the other one didn’t explode but was one hundred yards from my house. At that time there were no houses just fields.”

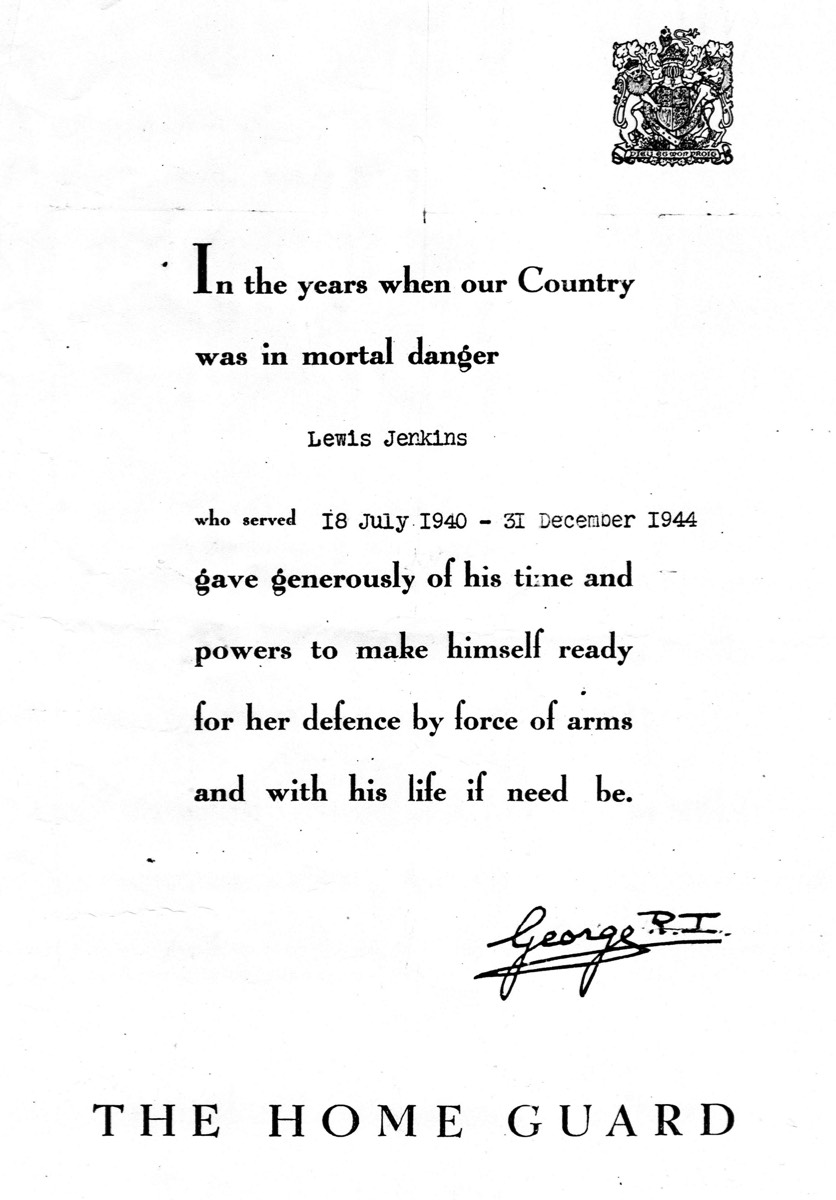

Official thanks for Lewis Jenkins’ Home Guard service.

Lewis visiting the grave of a fellow Newfoundlander in the churchyard at Abbey St Bathans. Simon Raymond Hancock, aged twenty-nine, died while swimming in a local river, 20th June, 1941.

A reunion memento of the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry

Unit held in Clarenville, Newfoundland, in 1995.

British Honduran Forestry Unit - “It was what you call ‘hard work’”

The call for workers skilled in forestry went out all over the Empire. We have seen that the Newfoundlanders answered the call but so did Australians and New Zealanders. British Honduras in Central America, another British colony, also supplied men for the Timber Corps. This country is now Belize and despite being smaller than Scotland, supplied some 539 men by the end of 1941. Simon Martinez, one of these, described the motives which lay behind the decision of some of Hondurans to cross the Atlantic. He said: “We, being Britishers, we volunteered to come. We didn’t want the mother country to suffer.” Amos Ford, another Honduran volunteer, hinted at more prosaic motives, when he said that the rumour went round that whoever didn’t go to join the Timber Corps would probably be conscripted anyway. An additional spur was provided by the serious levels of unemployment in the colony in 1939. At the other end some official and private disquiet was expressed at the thought of bringing Honduran labour to Britain: the Chairman of the Forestry Commission believed the introduction of coloured labour into the UK would be “...unworkable.”

Perhaps not unconnected, the British Honduran unit was not maintained for as long as the others and ceased operations in 1943. The conditions the men faced in some of the work camps would appear to have been very basic, as one visiting official, touring the camps in February 1942, found them to be ‘...little more than prisoners' compounds’ with the men ‘...in an almost mutinous condition.’ 1 Unfortunately the third contingent to come from British Honduras was aboard S.S. Svend Foyn, a ship torpedoed and forced to limp to Reykjavik, Iceland, though thankfully without any loss of life. However, the mens’ belongings were lost and this meant that they arrived in Scotland in a full-blown Scottish winter with only what they stood up in. Since the camps didn’t have electricity, hot water or even adequately insulated huts, the lack even of a change of clothing meant the men affected had no choice but to dry off their wet clothing through their own body heat.

A contingent of the the Hondurans came to set up a camp on an isolated field on Beil Grange Farm, East Linton, in September, 1941, a camp which became known as Traprain Law Camp. At first the men were rather scathing as regards the timber they were expected to fell. According to Amos Ford many of them were more used to felling huge mahogany trees back home and compared to these, the Pines were mere ‘matchsticks’. Charlston (Chad) Savoury and Edward Philips were in this contingent of approximately 100 men. Initially they had to spend some weeks under canvas as their huts hadn’t been completed. This whole experience, of course, meant not only a severe culture shock but a major climatic one too! There were even problems with the food: men from British Honduras were used to a diet with ample supplies of sugar (rationed in the UK) and both the men and their cooks were unused to dealing with lamb or mutton.

“The Coalmen Are Coming!”

However, the Hondurans settled in and made contact with the locals both in East Linton and, a longer walk away, in Haddington. Overall relations were pretty good and the Hondurans scored a local hit with their music-making abilities. Jimmy Christie, a Honduran trumpet player, was invited to play at functions in the village and church at Spott while the men attended nearby dances and socialised with the inhabitants, many being welcomed into their homes in their free time. Some of the locals undoubtedly felt sympathy with men so far from home.

Not unexpectedly, of course, in a fairly conservative part of rural Scotland, the arrival of the Hondurans produced mixed reactions among the villagers, many of whom had never seen a coloured man before. Some were under the impression that the men came from Africa and couldn’t understand how they spoke English. Some small-scale trouble did rear its head when amorous relations with a small number of the local women caused friction and some of the local clergy initially thought it might be a good idea if East Linton and Duns were ‘...put out-of-bounds’. 2 However, there was little real cause for concern and the situation soon stabilised. Mr Keith, of the Colonial Office, “...minuted, that ‘putting the villages out-of-bounds is quite unnecessary...the men have established happy relations with the local people and are popular with them. [There was] nothing that need cause us concern.’”3 A former minister at Stenton, Dr MacKenzie and his wife, went to the camp every Sunday night and took a service for the men.

In sport some of the Hondurans had significant successes. Chad Savoury was a good boxer and won a number of bouts around Scotland, including two in Glasgow. He later became a Scottish champion. An E.H. Sampson gained third place in the Powderhall athletics handicap race out of 154 competitors in 1945.

[NOTE: “Treefellers” - A short film about the British Honduran Timber Corps was produced by Sana Bilgrami and directed by Robin MacPherson in 2004. The film, in the ‘This Scotland’ series was sponsored by scotlandspeople.gov.uk]. Click here to access the film - https://vimeo.com/364780261

1 Marika Sherwood, ‘The British Honduran Forestry Unit in Scotland, 1941-43 (One Caribbean (O.C.) Publishers), p. 10

2 Marika Sherwood, ibid. p. 30

3 Marika Sherwood, ibid. p. 30

Eyewitness: Margaret Powell

Margaret Powell, sister-in-law of Cleveland ? wrote the following description of the Hondurans in East Lothian:

"When they left their homes to come here they were issued with fur coats for the cold but as soon as they got here they were taken off them and they were given navy blue battle dress uniforms, two woollen vests and two long underpants and a navy overcoat. They had no scarfs or anything to keep them warm. [Nor, in many camps, did they have the means to dry wet or washed clothes - ed]

In 1941, when we had the very bad winter, the men had to walk from camp to East Linton and carry the boards of bread back to camp. They were paid nine pence old money for scaling and felling a tree. One Bigwig came out from Drumheugh Gardens in Edinburgh to make a suggestion about wages. He said, 'why don't we pay you ten cents [sic] per tree instead of nine pence.' The men went mad. He thought they did not understand their money.

Cleveland used to use a big horse to pull the trees out of the forest to be loaded. [On one occasion] when they finished work he had to stable the horse so he was late for dinner and … got none. He then helped himself and took two slices of dry bread and a piece of cheese so the cook had ten shillings deducted from his wages.

How, off these wages, [were] they [expected]… to pay so much for the uniform and also leave money to be sent home to their people? When they came they had to put up their own huts and in each hut there was one little stove: it would hardly heat a kitchenette. If they were ill there was one man in camp who called himself a doctor, but he was no doctor, just a male nurse in his own country. ...a taxi used to run from East Linton to the camp, cost 1/= (5 pence).

When my sister and Cleveland went to get married they were the first. The Registrar in Tranent refused to marry them because Cleveland was black. His name was Fotheringham. They got married in church at Gladsmuir by Rev. Wiseman.

The cook in the camp was Donald Gable and when the camp broke up he was praised by the Big Wigs for saving £100 worth of tea and rations that was the mens’ food. It was in the Edinburgh Evening News. When Cleveland came his three uncles and his great uncle came as well and quite a few cousins. The Great Uncle was about seven feet tall. Cleveland (Clive) won the Golden Gloves before he came here at the age of seventeen.”

A band formed from the Honduran Timber Corps playing in Tranent.

The drummer is Winston Strudy Sebastian.

Chad Savoury, David Haire [Editor] and Ernest Philips visiting the graves of the three members of the Traprain Law Camp who died in East Lothian. Whittingehame Parish Church, 26th April, 1998.

H. P. Moss.

H. Valasquez.

I. Mendoza.

Women’s Land Army Timber Corps

Nearly 5,000 women served in the Women’s Land Army Timber Corps during the war and a number of them worked in East Lothian. Alison McLure spent some time in the Timber Corps and worked in the sawmill at Tyninghame. Here she describes her experiences:

"[I came up with my friend, Mary Crawford,] from Minto Estate, near Denholm, Hawick.

Maimie and I cycled over to the sawmill at Tyninghame each morning to hear the engine keeper giving a warning blast to start work at seven o'clock. There we stacked blocks of wood of varying shapes and sizes, helped to load lorries, and at one point I had to feed the sawmill engine with logs to keep the heat up. If one turned one’s back on it for a moment, it seemed, it gave one a sharp reminder that the water level was running low and that it needed to be loaded up again with logs.

On one occasion when I was on the cutting duty at a circular saw, I had bent down to look at some logs at my feet, Fortunately for me I was wearing gloves, which normally we were advised not to do. The next thing I heard was ‘zzzzz’! I was petrified, but the saw had only cut the top of my glove off as the log had been pushed towards the saw by the man who was working with me... I had inadvertently turned my head away and he had thrust the tree forward.

My friend and I helped to remove a large tree at one point in the wood and it was realised by the foreman, a Mr Sutherland I think his name was, that we had been used to handling heavy logs. The work was very hard but I am glad of the time spent in the Timber Corps rather than [in] munitions or in the Forces. Being in the countryside working outdoors suited me and, of course, the wartime conditions meant it was a case of ‘all hands on deck’ to help win the war. Looking back I am glad I was able to add my little bit to the war effort.”